Breadcrumbs navigation

Prague: astronomical

Time in the City passes in its own sweet way. It has its own dynamic, dawdling or hurrying, as if taking its cue from some postulates Einstein left behind. Not nearly as impossible as it sounds. Prague abounds with places imbued with physics and astronomy history.

There is more truth to the mystical nature of Prague than even the promotional flyers dare hint at. Inside its ancient dwellings, compasses charted stellar constellations, dowsing rods marked the apotheosis of elixirs, and philosophers, astrologers and skilled watchmakers tried to tame time’s mercurial elusiveness. It must all have left a powerful imprint on the City’s esprit. In truth, a number of earnest astronomers and physicists, including Albert Einstein, still cited by modern science, called this city their home. In Prague, Tycho Brahe served as the court astrologer to Rudolf II; while his assistant Johannes Kepler formulated laws on the circumsolar movement of the planets. As for Albert Einstein, he lived in Prague for a year and a quarter, and his stay here brought eleven scientific works to the world. The pride of the city is the completely unique astronomical clock from the 15th century, which measures time in several ways and its ingenious mechanisms tell, inter alia, of the current position of the planets as seen from the northern or southern hemisphere. And there’s plenty more …

Meridian-minded lunch time

Whatever brings you to Prague, it’s winding streets will eventually bring you to Old Town Square. In sunny weather, you may notice a beam of light reflected off the Prague Meridian – a brass bar set into the flagstones at 14°25′17″ East of the Greenwich Meridian. There was a very down-to-earth reason why Prague citizenry set this into the main square in 1652, not just for fun, but to give a reliable sign the Sun was at its height, and it was time for lunch. The needed only to keep an eye on the shadow of the erstwhile Marian column touching the Meridian. More sophisticated timings at the Prague Clementinum showed that the shadow and the Meridian coincided accurately to within one second. Although you’re unlikely to see anyone set their watch by the Prague Meridian today, its former role is testified by the 1990s Latin inscription ‘Meridianus quo olim tempus pragense dirigebatur’ (The Meridian that in bygone times set Prague time.) The other technical and astronomical piece of heritage on Old Town Square, the peerless Prague astronomical clock has prompted countless articles and studies, so let us gloss over it this time and refer the reader to a separate entry HERE.

Starry secrets

Prague had enjoyed its own astronomical clock for some 150 years by the time Emperor Rudolf II called master Tycho Brahe to Prague. The Danish astronomer spent only two years working at the Hapsburg court, but he formulated his basic laws of celestial mechanics all the sooner for it, albeit not without errors. His observations of the stars led him to deduce, correctly, that the planets orbit around the Sun, but he was mistaken in thinking they also circled the Earth. The geocentric celestial mechanics approach gave way only to the principles formulated by a student of Brahe – Johannes Kepler. Mystery still surrounds the death of the Danish scientist (in 1601). Rumours spoke of stress and kidney disease, but also of poisoning by the mercury he used in alchemical experiments. According to a more frivolous view of history, he died of a ruptured urinary bladder, because he dared not ask to be excused during an audience with the emperor. A recent exhumation of Brahe’s mortal remains has ruled out the mercury poisoning theory, but confirmed a high level of gold in his hair, beard, and eyebrows. It follows that gold must have featured greatly in the astronomer’s life, but surely it was nothing to die of. “Gold was ubiquitous throughout the higher social circles of Renaissance Europe. It featured in clothing, jewellery or cutlery, even in the meals themselves. Gold flakes were also intentionally added to wine, in the belief that people could be imbued with a ‘divine principle’ through precious metals”, the researchers recounted. The exact cause of death of the renowned scientist thus remains a mystery.

Science unearthed at Pohořelec?

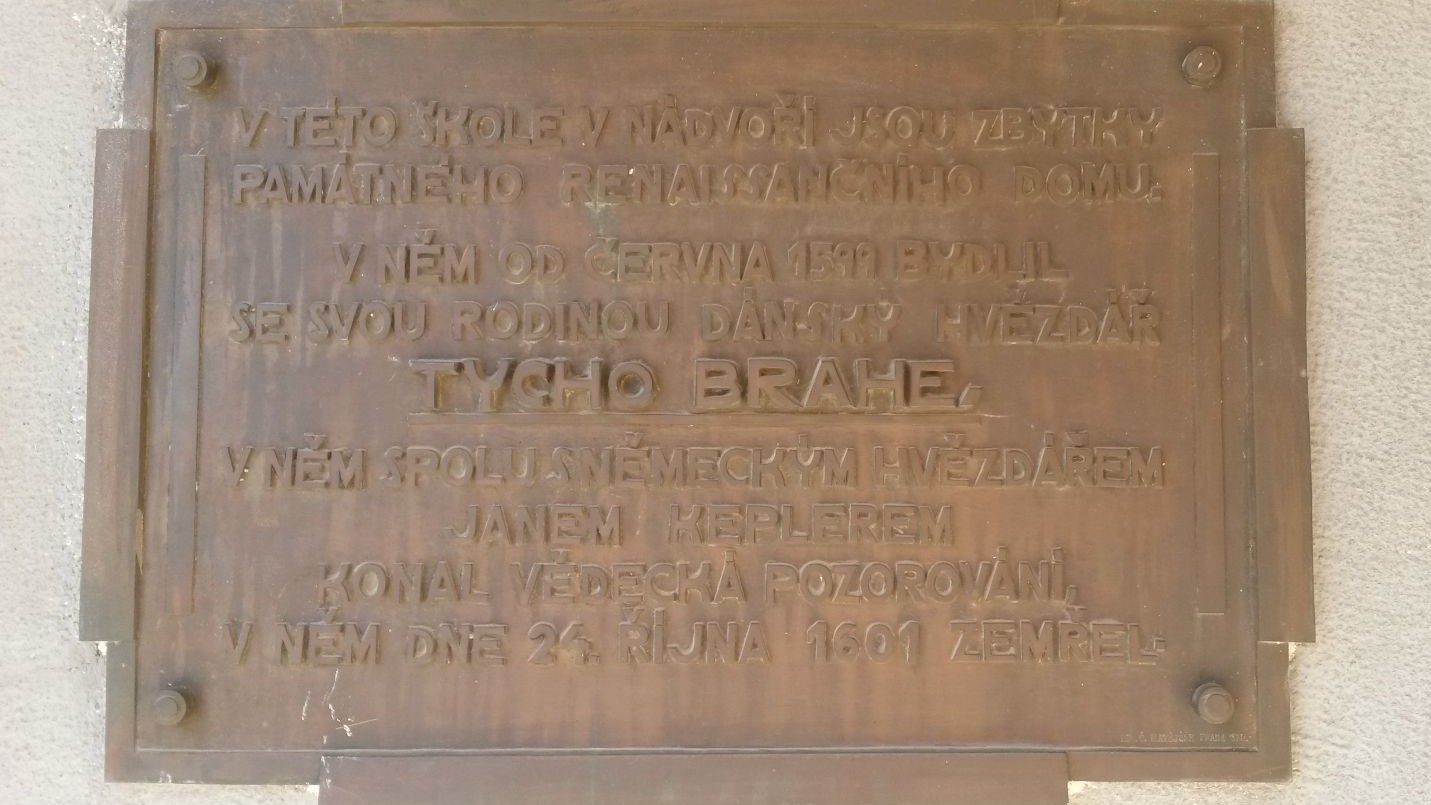

Whether or not the vaunted boffin’s demise was down to strict observance of courtly etiquette, the riskier elements of his research, or natural causes, his name is indelibly linked with Prague at the turn of the 16th and 17th centuries. Tycho Brahe’s body is buried in the Church of our Lady before Týn by the first right-hand nave pillar, and it is a great pity that the tomb remains an underrated tourist attraction. Also scarcely known is the fact that in 2005, a dig in the gardens of the Jan Kepler grammar school at Pohořelec revealed and confirmed the remnants of the house where Brahe is recorded to have lived (later with Kepler), where he conducted his astronomical observations, and ultimately died. The low wall of arenaceous marlstone that can now be seen in the school grounds reminds of the existence and location of the astronomer’s residence. There is also a commemorative plaque to the famous scholarly duo of Tycho Brahe and Johannes Kepler at the establishment entrance, unveiled in 1946. Another interesting memento is the sculpture of the two natural philosophers, by the academic sculptor Josef Vajce, erected at the school in 1984.

![]()

The famed Dane’s death did not quell the study of the solar system, however. As mentioned, in 1600 Johannes Kepler, the German mathematician and astronomer came to Prague, as Tycho’s assistant. After his mentor’s death he published the Astronomia Nova, based on his notes, which gives Kepler’s first two laws on planetary motion around the Sun. Small-sized exposition in the area in front of the entrance to the roof of the National Technical Museum depicts Kepler’s stay in Prague. It is accessible within educational programs, after ordering at e-mail pedagogika@ntm.cz. On the well-arranged panels you can learn about life, discoveries and writings of the famous astronomer. The exhibition thematically follows the "Astronomy" exhibit.

Whither for the weather

Time-keeping and planet-tracking were soon followed by weather mapping. It was all grist to the mill for the Jesuits, who developed commendable science and education initiatives in Prague. Their college in the Clementinum with its regular local climate readings of temperature, atmospheric pressure, rain and snowfall patterns began in 1775 and the metrics and statistics there continue to this day. Interest in the Jesuits’ meteorological work grew notably in the 1930s, when scientists around the world began to pay close attention to climate fluctuations. Indeed, even two-hundred-year-old records were a rare and extremely valuable source of information for modern climatology. It cannot be denied that the Jesuits showed great prescience, given their temperature and air pressure readings were taken twice a day from the outset, always at sunrise (in the summer, two hours after sunrise) and in the afternoon around 3 pm.

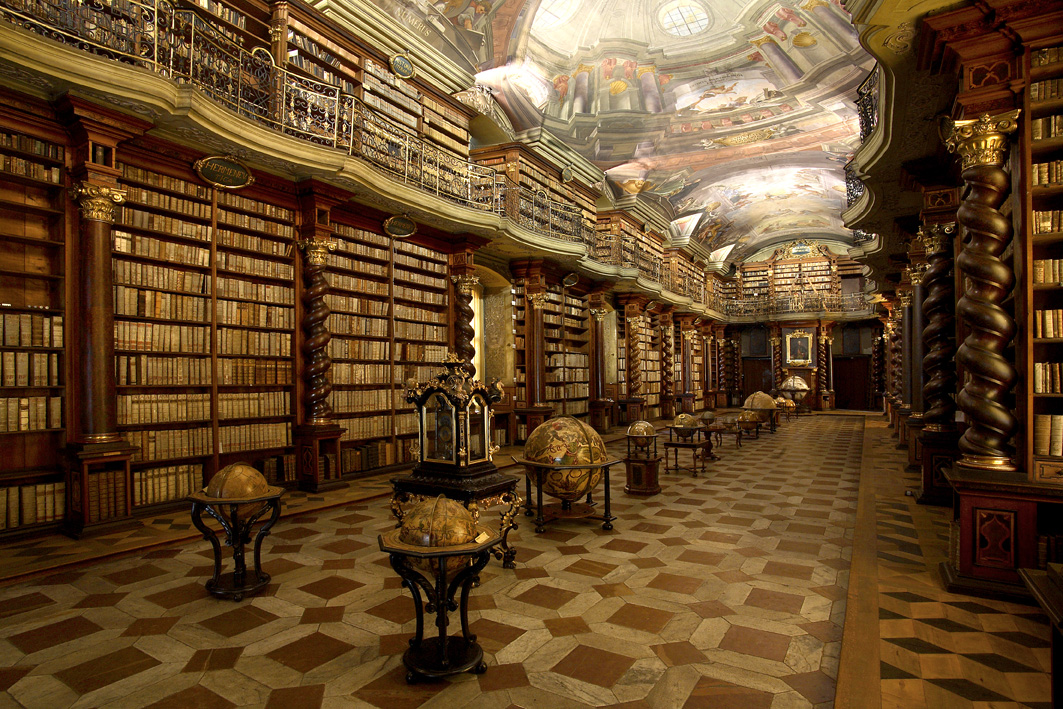

Exclusively guided daily tours of the Clementinum (including weekends and public holidays) go every 30 minutes from 10 am, for 20 people max. During the 50-minute visit you will see the Meridian Hall (formerly used for the precise determination of noon), the Baroque Library Hall with numerous geographical and astronomical globes and and of course the unmissable Astronomical Tower. A unique feature of the Baroque complex is the Mirror Chapel, also accessible as part of the guided tour. This aspect cannot be guaranteed in advance, however, since the opulent room is often the venue of cultural and social events.

Einstein’s Prague

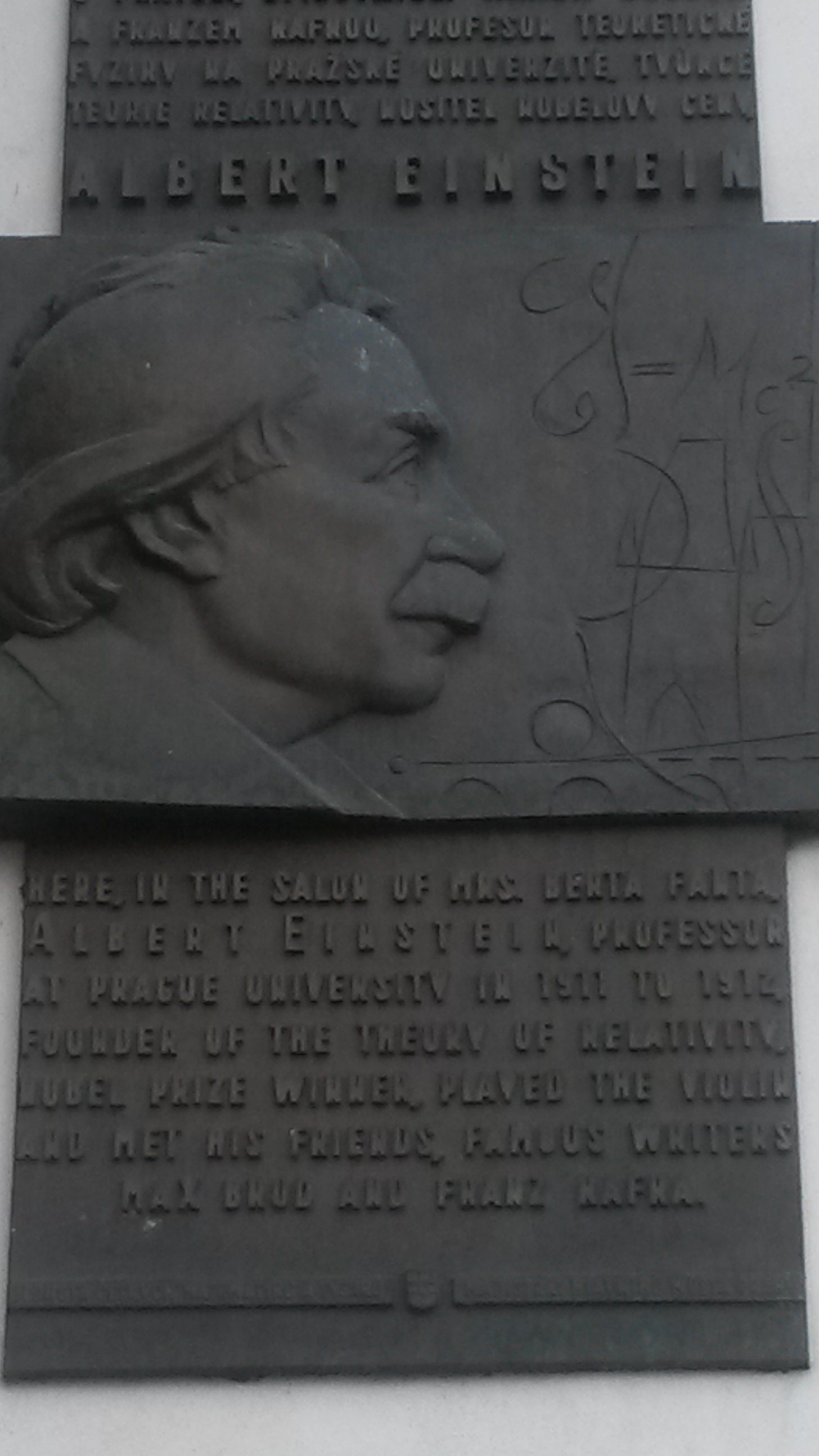

Our capital city also fondly remembers Albert Einstein, who unassumingly left science a bountiful legacy of definitions on the nature and relationship of time and space. And what links this Physics professor and world-renowned scientists to Prague? His personal records carry various remarks made with some admiration: “The city of Prague is beautiful, so beautiful, that it well deserves making a lengthy journey.” By contrast, other sources mention his being quite critical of the Prague environment (especially the air). Not to have a plaque in Prague to the man whose E=mc² is not unheard of even among schoolchildren would be quite unthinkable. One commemorative plaque hangs on the House at the Unicorn on Old Town Square, where Einstein used to play the violin in the salon of Berta Fantová, and met with Max Brod and Franz Kafka (in 1911-12). Another can be seen in the Smíchov district in Lesnická street, where Einstein stayed while in Prague, Einstein lived and a third adorns the building of the Natural Science Faculty, where the physicist gave lectures.

Reversing time, or the Jewish mirror

In Prague’s Jewish Town, you will find that even the commonplace can have its unusual side. On the Tower of the Jewish Town Hall (one of the oldest in Europe, still used for worship) reportedly bears the oldest Hebrew clock in a public place. This is significant in and of itself, but far from extraordinary. You may find it mildly surprising that there are Hebrew characters instead of digits. Somewhat more astounding is the finding that the digits are reversed, so that the Jewish clock has a nine where you’d expect the three and so forth. Then you surmise that Jewish clock hands must move anticlockwise, leftwards. After a moment’s thought on how to read the time, you get the idea that this clock also has its small and large hands swapped around. You have been warned, time in Prague can take altogether unexpected turns …

To the stars, via Stromovka Park

Present-day astronomy in Prague is chiefly represented by the observatories (the Štefánik on Petřín Hill, and in Ďáblice) and the popular Planetarium in today’s Stromovka. Its main attraction is the projection room with its spherical ceiling (cupola), representing the putative heavenly dome. Projected onto this ceiling are the various celestial objects and their trajectories in space and time; also shown are a host of images, videos and animations. Viewers get to sit in theatre- or cinema-style comfortable seats, and watch a perfect illusion of daytime or nocturnal skies on the dome – at 23.5 metres across one of the largest in the world. The Planetarium is equipped with state-of-the-art technology and is without exaggeration a genuine ‘Stargate’ into the depths of the universe.

Authors: Jan Pomykal, Prague City Tourism; Hana Čermáková (C.O.T. media)