Breadcrumbs navigation

Josef Mysliveček

Today, Mysliveček is regarded as one of the landmark musical figures of European history. Legends about his life inspired books, opera and films. Streets in several Czech cities are named after him (in Prague, Myslivečkova street is in Petřiny in Prague 6) as well as an asteroid in our Solar System. Prague is also proud to be associated with him.

Back in 1737, the 29-year reign of Habsburg monarch Charles VI was slowly drawing to a close and the Austro-Turkish War began. In Italy, the ancient city of Herculaneum near Naples was rediscovered. At the instigation of King Charles III, a new theatre, the Teatro San Carlo, opened in Naples, soon to become the most prestigious opera house in all of Italy. In the same year a future composer was to be born in Prague, who would later perform a number of successful operas, composed in honour of Charles III and his family.

On Tuesday 9 March that year, 31-year-old Anna Terezie Myslivečková, née Červenková, gave birth to twins Josef and Jáchym in Sova’s Mills on Kampa, and everyone in her circle expected them to go on to become good millers. They were not going to disappoint – the sons of the venerable master miller Matěj Mysliveček did actually go on to learn the craft. While Jáchym took it up for the rest of his life, Josef did so only until he was twenty-five. He then turned to music and became the most famous Czech composer of the 18th century.

This happened quite unexpectedly. Probably at the instigation of his ambitious father, Josef and Jáchym first attended the Dominican school at St Giles, followed by the Klementinum Jesuit College (getting high quality musical training) and finally they enrolled at the Charles-Ferdinand University, but would not last even a year there. They then trained in the miller’s art and were accepted into the Prague guild, as master millers. They were all set to join in with the family business.

However, the clapping of the millwheel was not the only rhythm that young Josef Mysliveček would listen to. In 1763, the Seven Years’ War ended. It did not redraw a single border on the map of Europe, so half a million soldiers and half a million civilians had died in vain; but after that Italian operas began returning to Prague. Probably also under their influence, Mysliveček decided to return to music, which he was already versed in by the Dominicans. He began deepening his musical education in Prague, but felt drawn to Italy, the cradle of opera, like a number of other talented musicians from the Czech lands, including Ch. W. Gluck or Florian Gassman. Thanks to the support of his patron, Vincenc of Wallenstein, he set out for Venice in 1763. In less than three years, his first opera was being performed.

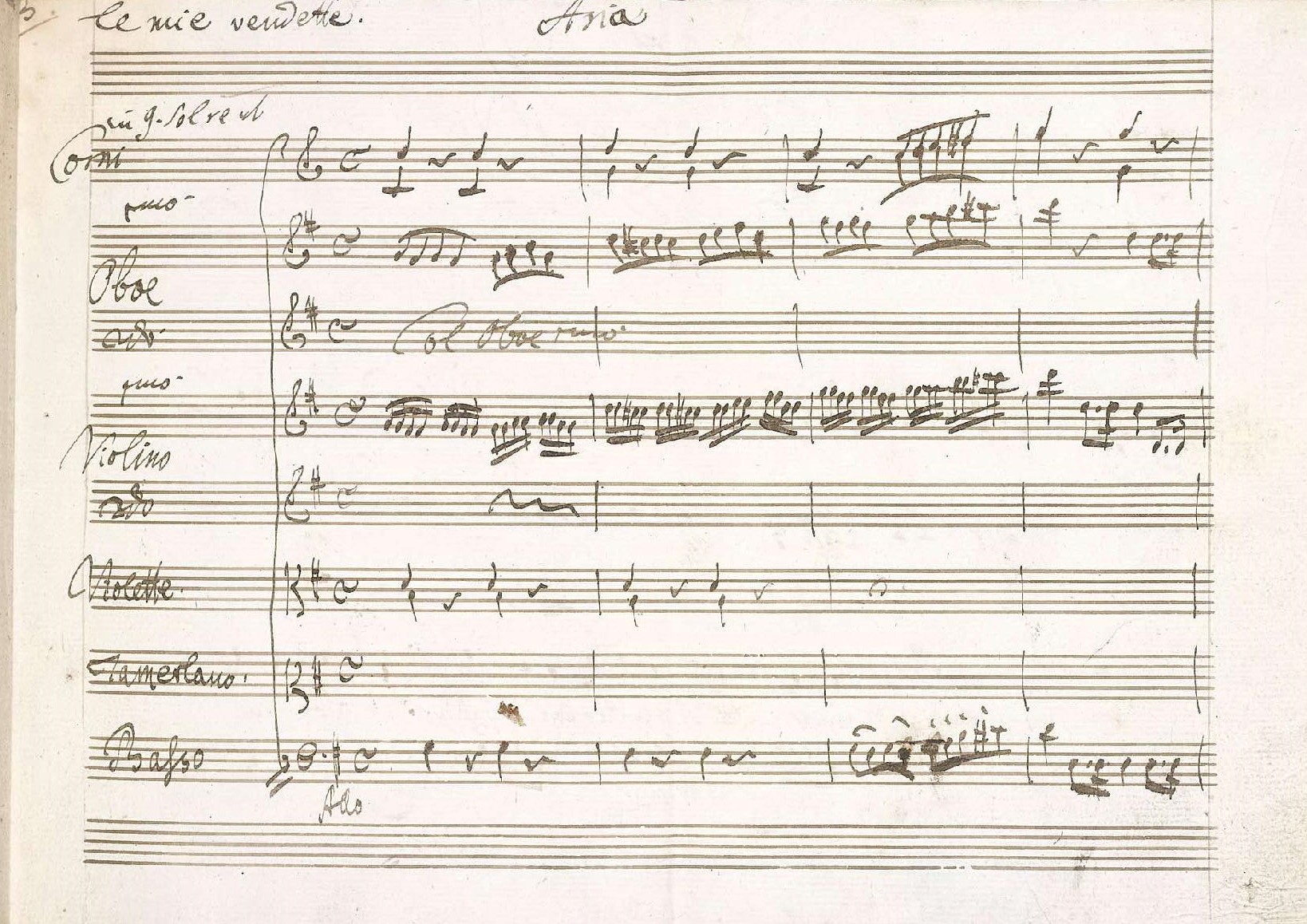

Although it wasn’t immediately staged in more prestigious Venice, but in nearby Bergamo, it brought enough acclaim for Mysliveček to be invited to write an opera for Naples. Called Il Bellerofonte, it played at the Teatro San Carlo, the most prestigious European operatic stage of its time. Mysliveček’s star was on the ascendant, writing operas for Florence, Rome, Venice, Turin, Bologna, but he remains most linked with Naples.

Although it wasn’t immediately staged in more prestigious Venice, but in nearby Bergamo, it brought enough acclaim for Mysliveček to be invited to write an opera for Naples. Called Il Bellerofonte, it played at the Teatro San Carlo, the most prestigious European operatic stage of its time. Mysliveček’s star was on the ascendant, writing operas for Florence, Rome, Venice, Turin, Bologna, but he remains most linked with Naples.

It was in Bologna that he met Mozart in 1770, guiding and inspiring him to a considerable extent. When Mozart wrote his first proper Italian opera in three acts, Mitridate, re di Ponto (Mitridates, King of Ponto), he borrowed musical ideas from Mysliveček’s opera La Nitteti. Mozart, a generation younger, felt an affinity to Mysliveček; and visited him in the hospital in Munich when he was struggling with the consequences of STD, seven years later. That was the last time the two composers met. Mysliveček was to live only another four years.

These were marked by the composer’s progressive decline. Ravaged by his disease, probably syphilis, he suffered material deprivation. In 1778 he put on one of his best operas, L’Olimpiade, with great success, but his Armida a year later was a flop. The increasingly ill composer was to complete two more operas, in great pain. He died in Rome at the beginning of February 1781, completely destitute and looking like a haggard old man. Yet he was only 43 years old.

More about the life and work of Josef Mysliveček can be found here.